In the third post of this series we have discussed an idea of I. Rivin (see [1], [2]). Rivin has shown that the surface area of a general (n-1)-dimensional ellipsoid in a n-dimensional Euclidean space can be expressed in terms of an expectation value of a specific function weighted by a multivariate Gaussian probability density [pdf]. In contrast to (n-1)-spheres and n-balls, the ratio between the surface area of a (n-1)-ellipsoid and its enclosed n-dimensional volume is given by a complicated expression.

One can show that already the determination of the surface area of a 2-dimensional ellipsoid in the ℝ3 requires the (numerical) evaluation of complete and incomplete elliptic integrals; see [9] for details. For n-ellipsoids one must either evaluate a Lauricella hypergeometric function (series) [10] or Abelian integrals [11]. Rivin’s formula instead allows for a numerical calculation of the surface of (n-1)-dimensional ellipsoids by averaging data of a specific function multiplied with the pdf of a standardized Multivariate Normal distribution [MVN]. This finding links statistics and geometry in an exciting way.

In this post we will show that Rivin’s ideas really work. At least for low-dimensional ellipsoids. For ellipses and ellipsoids in the ℝ3 very good approximation formulas are available; see e.g. a discussion by J.D. Cook in [3] and [4]. We will use these approximations below in numerical experiments and compare their results to Rivin’s expectation values for ellipses and ellipsoids in a 3-dimensional space. We will find a very good agreement.

Previous posts in this series:

- Post 1: n-dimensional spheres and ellipsoids – I – Gamma-function, volume and surface of n-spheres

- Post 2: n-dimensional spheres and ellipsoids – II – volume of n-ellipsoids

- Post 3: n-dimensional spheres and ellipsoids – III – Surface area of n-dimensional ellipsoid and its relation to MVN-statistics

Reminder – Rivin’s formula

We define a (n-1)-dim ellipsoid with semi-axes ai (i ∈ [1,n] ) in the (Euclidean) ℝn by

Note: This description implies a special choice of a Cartesian Coordinate System [CCS], namely one whose coordinate axes are aligned with the ellipsoid’s n main axes. In addition, the ellipsoid’s geometrical center must coincide with the CCS’ origin.

The “(n-1)” refers to the dimensionality of the ellipsoidal manifold. Rivin claims in [1], [2]:

where the expectation value is given by

This means that we have to average the square root for a probability density of n independent Gaussians of a very elementary standardized and thus radially symmetric MVN (covering all of the ℝn).

How can we check the formula numerically for ellipsoids and ellipses in the ℝ3?

Below we will use a 4-dim MVN to first create four different 3-dimensional MVNs [3D-MVNs]. Afterwards, we describe the statistically generated vectors of each 3D-MVN in the main-axes system of the MVN’s concentric contour ellipsoids. A standardization of the resulting distribution of data points and respective vectors eventually allows for a numerical calculation of Rivin’s expectation value for any confidence ellipsoid defined by a distinct value of a Mahalanobis distance. For ellipsoids and ellipses, there exist very good approximation regarding the surface area and the perimeter, respectively.

Exact formulas for the perimeter of an ellipse and the surface area of an ellipsoid in a 3-dim space

We find the exact formula for the perimeter of an ellipse S1,ell in terms of a complete elliptic integral Ec in [6]:

Perimeter of an ellipse

Ec(e) represents the complete elliptic integral of the second kind. e is the ellipticity of the ellipse. The SciPy library provides functions to calculate Ec with a high degree of accuracy.

C. Hill gives an exact formula for the surface of a 2-dimensional ellipsoid in the ℝ3 in terms of incomplete elliptic integral of the first and second kind (see [9]):

Surface of an ellipsoid in the ℝ3

In this formula a, b, c represent the semi-axes, with a being the largest and c the smallest semi-axis (!). So, to apply the formula you first have to order the semi-axes. K(Φ,k) and E(Φ,k) represent incomplete elliptic integrals of the first and second kinds, respectively. The SciPy library provides functions to calculate these integrals with a high degree of accuracy.

Below, we will take the above formulas (in their SciPy approximation) as the standard values with which we compare the results of numerical evaluations of Rivin’s formula.

Approximation formulas for the surface areas of ellipsoids and ellipses

A physicist, J.D. Cook, has written about approximation formulas for the surface areas of ellipsoids in 2 and 3 dimensions (see [3] and [4]). For an ellipse with semi-axes a and b Cook cites the following approximation of Linderholm and Segal [5]:

Approximation 1 for the perimeter of an ellipse

We find another approximation of Ramanujan at Wikipedia [6]:

Approximation 2 for the perimeter of an ellipse

For a 3-dimensional ellipsoid with semi-axes a, b, c, J.D. Cook [4] and also G.P. Michon [7] name a formula given by Knud Thomsen (2004, see [7] ). You find this formula also on Wikipedia [8]:

Approximation for the surface of a 3D-ellipsoid

Another approximation is discussed by C. Hill in [9]

So, we have a variety of approximations to choose from.

Setup of the numerical experiment

Below, we call the main-axes CCS of a MVN’s contour ellipsoids the “MVN’s main-axes system”. To test Rivin’s formula we use the following setup and steps:

- Step 1: We use a (4×4)-covariance matrix to create a 4-dimensional MVN in the (Euclidan) ℝ4 . The main axes of this 4D-MVN’s ellipsoids are rotated against the CCS’ coordinate axes. The creation of respective data points is done with the help of Numpy’s function random.multivariate_normal().

- Step 2: We project the 4-dim MVN down to 4 different 3-dimensional ℝ3 sub-spaces of the ℝ4. The projection is done to sub-spaces orthogonal to the 4 coordinate axes. These projections give us four 3-dimensional 3D-MVNs. The axes of their contour ellipses are rotated against the coordinate axes of the 3-dim sub-space.

- Step 3: For the 3-dim MVNs we can get their (3×3)-covariance matrices [cov-matrices] by selecting related elements out of the original (4×4) matrix. The selection corresponds to the application of a projection matrix.

- Step 4: From the eigenvalues of the (3×3) cov-matrices we can evaluate the semi-axes of related contour ellipsoids or confidence ellipses given by some Mahalanobis distances dm.

- Step 5: From the eigenvectors of each (3×3) cov-matrix we get the rotation matrix required to describe the vectors of the 3-dim MVN in the MVN’s main-axes system. (The coordinate axes of the respective CCS for the 3-dim sub-space are then aligned with the main axes of the concentric contour ellipsoids.) We transform all the vectors given for the generated data points of each 3-dim MVN into the its main-axes CCS. We also use the rotation matrix to transform each 3D-MVN’s covariance matrix into its main-axes coordinate system. This corresponds to a diagonalization.

- Step 6: We standardize the four 3-dim MVNs in their main-axes system and get respective spherically symmetric MVNs of decoupled independent Gaussians. As we are already in the main axes system of each of the 3D-MVNs, this operation corresponds to simple divisions of the coordinate values by a respective eigenvalue of the transformed cov-matrix.

- Step 7: Step 6 allows for the calculation of the required evaluation value in Rivin’s formula, which we compare with results of independent (approximation) formulas (6), (9) and (10).

Note: The change to the main-axes system of each 3D-MVN in step 5 is an essential operation. Note further that during step 7 the numerical averaging is done via the number of data points.

Afterward we do something analogously with projections on 2-dim sub-spaces of the ℝ4. This then gives us 6 different 2-dim MVNs, which we use to test Rivin’s formula for the perimeters of respective confidence ellipses. We compare the results to formulas (5), (7) and (8).

As a starting point for step 1, we use the following (4×4)-cov-matrix:

The 4-dim MVN is constructed with the help of Numpy’s function random.multivariate_normal(). We create 40,000 data points and respective vectors. The projections leave the number of points unaffected.

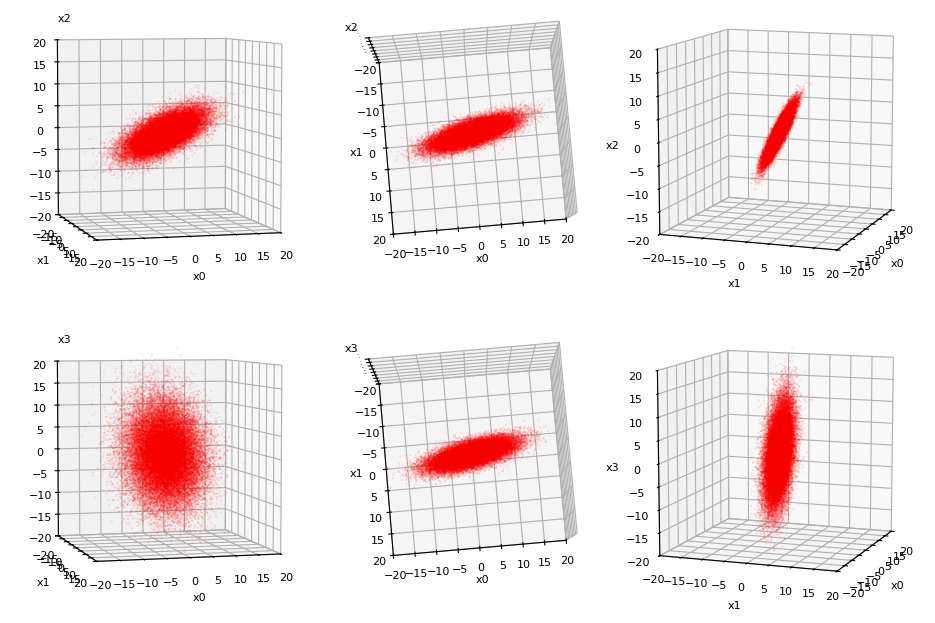

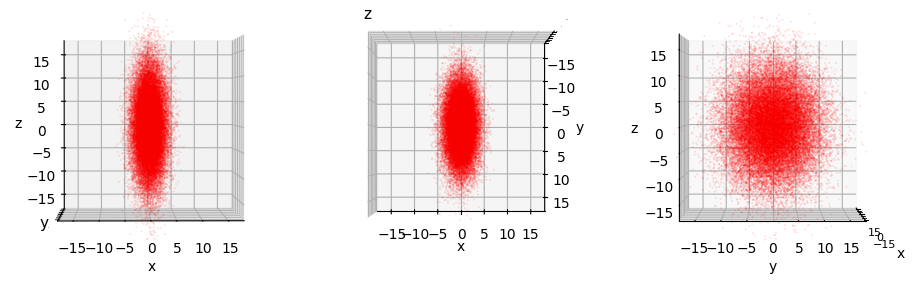

Plots and results for the surface areas of 4 ellipsoids

Below you find the 3-dim projections. Each line shows one of the four 3D-MVDs from 3 different perspectives. The 4 coordinate axes of the 4-dim space were named x0, x1, x2 and x3.

The real character and the differences between MVNs and the orientations of their main axes will become clearer after a representation in their main axes systems; see below.

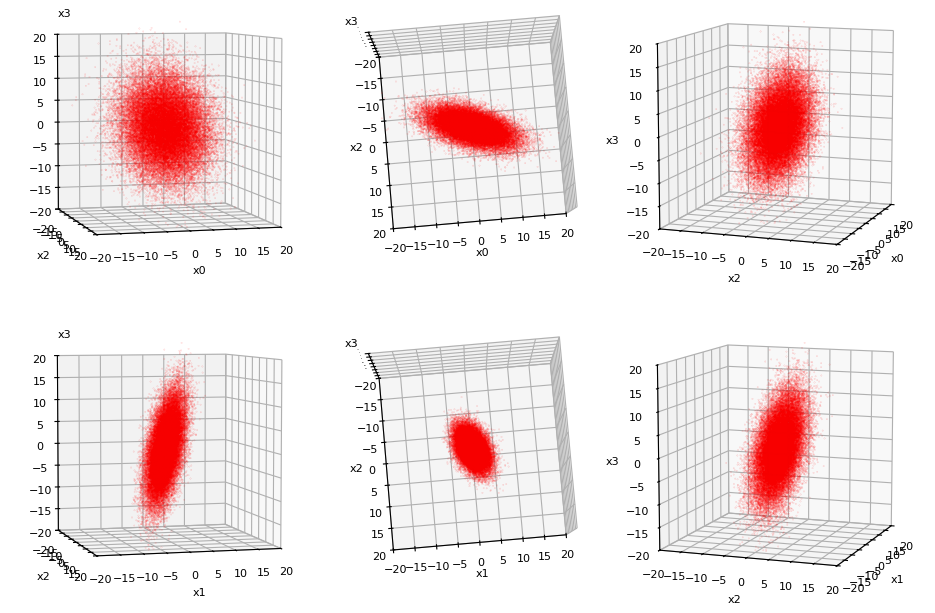

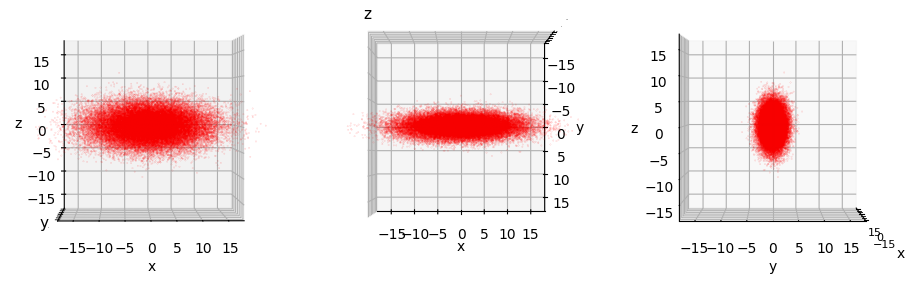

Main axes representations

In the same order as above the rotated 3-dimensional projection MVDs look like follows in their main-axes systems. Note that the axes have been renamed and the order of axes may be switched.

3-dim MVN 1:

3-dim MVN 2:

3-dim MVN 3:

3-dim MVN 4:

So, we really have 4 rather different ellipsoids shapes.

Note about the order of projection and rotation:

We have first projected the original 4-dimensional MVN and then rotated each 3-dimensional projection into the 3D-MVN’s main-axes system. For some tests this order has to be considered carefully during programming.

Table with results

The results in the following table depend a bit on the random generation and placement of the 4D-MVD’s data points. So two different runs may differ somewhat regarding relative deviations between the results. I started the generation of the 4D-MVD again ahead of calculating the data for another 3D projection MVN-x. The tables have the same order as the images of the 3-dim MVNs depicted above.

Concrete ellipsoids of the 3D MVNs were defined by distinct values dm = 0.5, 0.75, 1.00, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75, 2.00 of the Mahalanobis distance dm.

3-dim MVN 1:

| 3D-MVN | Formula | dm=0.50 | dm=0.75 | dm=1.00 | dm=1.25 | dm=1.50 | dm=1.75 | dm=2.00 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D-MVN 1 | Surface exact eq.(6) | 21.50625 | 48.38907 | 86.02502 | 134.41409 | 193.55629 | 263.45162 | 344.10007 |

| 3D-MVN 1 | Surface acc. Rivin eq.(3) | 21.47386 | 48.31619 | 85.89545 | 134.21164 | 193.26476 | 263.05481 | 343.58179 |

| 3D-MVN 1 | Surface approx1 eq.(9) | 21.68567 | 48.79276 | 86.74268 | 135.53543 | 195.17102 | 265.64944 | 346.97070 |

| 3D-MVN 1 | Surface approx2 eq.(10) | 21.24251 | 47.79565 | 84.97005 | 132.76570 | 191.18261 | 260.22077 | 339.88019 |

3-dim MVN 2:

| 3D-MVN | Formula | dm=0.50 | dm=0.75 | dm=1.00 | dm=1.25 | dm=1.50 | dm=1.75 | dm=2.00 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D-MVN 2 | Surface exact eq.(6) | 49.27788 | 110.87523 | 197.11151 | 307.98674 | 443.50090 | 603.65401 | 788.44605 |

| 3D-MVN 2 | Surface acc. Rivin eq.(3) | 49.36350 | 111.06789 | 197.45402 | 308.52190 | 444.27155 | 604.70294 | 789.81608 |

| 3D-MVN 2 | Surface approx1 eq.(9) | 49.55488 | 111.49848 | 198.21952 | 309.71799 | 445.99391 | 607.04727 | 792.87806 |

| 3D-MVN 2 | Surface approx2 eq.(10) | 47.55979 | 107.00952 | 190.23915 | 297.24867 | 428.03808 | 582.60739 | 760.95659 |

3-dim MVN 3:

| 3D-MVN | Formula | dm=0.50 | dm=0.75 | dm=1.00 | dm=1.25 | dm=1.50 | dm=1.75 | dm=2.00 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D-MVN 3 | Surface exact eq.(6) | 55.74462 | 125.42540 | 222.97848 | 348.40388 | 501.70159 | 682.87161 | 891.91394 |

| 3D-MVN 3 | Surface acc. Rivin eq.(3) | 55.77960 | 125.50410 | 223.11840 | 348.62249 | 502.01639 | 683.30009 | 892.47358 |

| 3D-MVN 3 | Surface approx1 eq.(9) | 55.95887 | 125.90746 | 223.83549 | 349.74295 | 503.62985 | 685.49619 | 895.34196 |

| 3D-MVN 3 | Surface approx2 eq.(10) | 53.07174 | 119.41142 | 212.28697 | 331.69838 | 477.64567 | 650.12883 | 849.14786 |

3-dim MVN 4:

| 3D-MVN | Formula | dm=0.50 | dm=0.75 | dm=1.00 | dm=1.25 | dm=1.50 | dm=1.75 | dm=2.00 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D-MVN 4 | Surface exact eq.(6) | 30.89089 | 69.50451 | 123.56358 | 193.06810 | 278.01806 | 378.41347 | 494.25433 |

| 3D-MVN 4 | Surface acc. Rivin eq.(3) | 30.89478 | 69.51326 | 123.57914 | 193.09240 | 278.05305 | 378.46110 | 494.31654 |

| 3D-MVN 4 | Surface approx1 eq.(9) | 30.88839 | 69.49889 | 123.55358 | 193.05246 | 277.99554 | 378.38283 | 494.21430 |

| 3D-MVN 4 | Surface approx2 eq.(10) | 30.34089 | 68.26701 | 121.36357 | 189.63058 | 273.06803 | 371.67593 | 485.45428 |

The numerical evaluation of Rivin’s formula obviously delivers excellent results. The relative error err_rel in comparison to eq. (6) is around or smaller than err_rel ≈< 0.002.

The 1st approximation acc. to eq. (9) also works very well. However, the second approximation acc. to eq. (10) comes with somewhat bigger relative errors in the range of some percent.

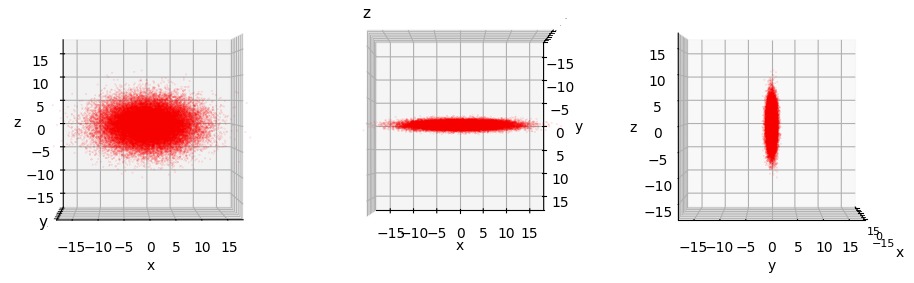

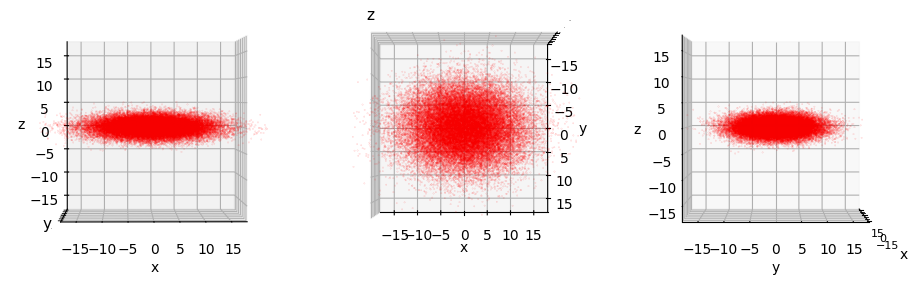

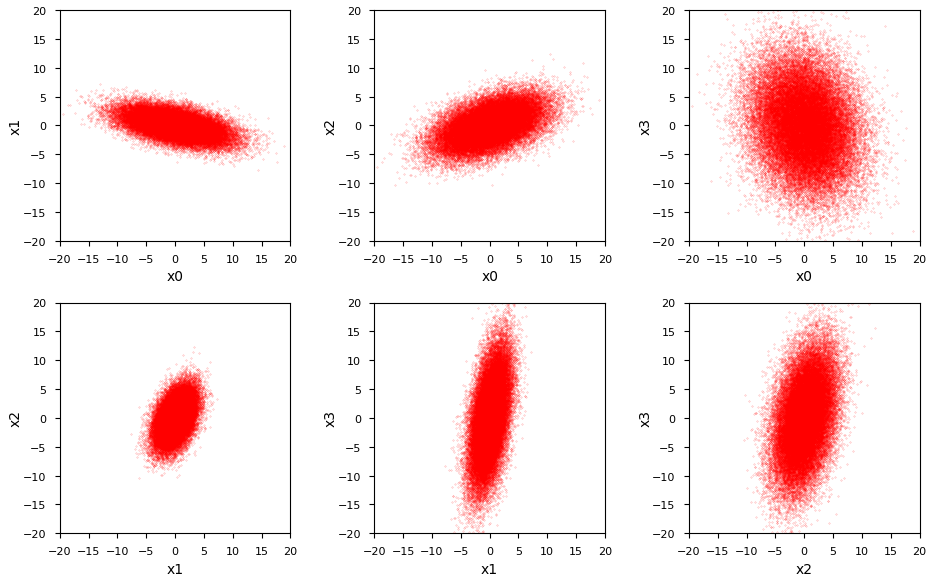

Results for 2-dimensional projections and the perimeters of respective ellipses

We now look at the six 2-dimensional projections onto coordinate planes and calculate the ellipses’ perimeters with the help of Rivin’s formula. The 2-dim projections are shown in the following illustration:

I omit images displaying the distributions in themain-axes systems of the respective contour ellipses of these six 2-dim distributions.

Concrete Contour ellipses are again defined via different Mahalanobis distances dm.

2-dim MVN 1:

| 2D-MVN | Formula | dm=0.50 | dm=0.75 | dm=1.00 | dm=1.25 | dm=1.50 | dm=1.75 | dm=2.00 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D-MVN 1 | Surface exact eq.(5) | 10.31620 | 15.47430 | 20.63240 | 25.79051 | 30.94860 | 36.10671 | 41.26481 |

| 2D-MVN 1 | Surface acc. Rivin eq.(3) | 10.30272 | 15.45407 | 20.60543 | 25.75679 | 30.90815 | 36.05951 | 41.21086 |

| 2D-MVN 1 | Surface approx1 eq.(7) | 10.30523 | 15.45784 | 20.61046 | 25.76308 | 30.91569 | 36.06831 | 41.22092 |

| 2D-MVN 1 | Surface approx2 eq.(8) | 10.31620 | 15.47430 | 20.63240 | 25.79050 | 30.94861 | 36.10671 | 41.26481 |

2-dim MVN 2:

| 2D-MVN | Formula | dm=0.50 | dm=0.75 | dm=1.00 | dm=1.25 | dm=1.50 | dm=1.75 | dm=2.00 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D-MVN 2 | Surface exact eq.(5) | 11.39554 | 17.09334 | 22.79109 | 28.48886 | 34.18663 | 39.88440 | 45.58218 |

| 2D-MVN 2 | Surface acc. Rivin eq.(3) | 11.38664 | 17.07996 | 22.77328 | 28.46659 | 34.15991 | 39.85323 | 45.54655 |

| 2D-MVN 2 | Surface approx1 eq.(7) | 11.39216 | 17.08823 | 22.78431 | 28.48039 | 34.17647 | 39.872546 | 45.56862 |

| 2D-MVN 2 | Surface approx2 eq.(8) | 11.39554 | 17.09332 | 22.79109 | 28.48886 | 34.18663 | 39.88440 | 45.58218 |

2-dim MVN 3:

| 2D-MVN | Formula | dm=0.50 | dm=0.75 | dm=1.00 | dm=1.25 | dm=1.50 | dm=1.75 | dm=2.00 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVN_3 | Surface exact eq.(5) | 16.66409 | 24.99613 | 33.32818 | 41.66022 | 49.99227 | 58.32431 | 66.65636 |

| 2D-MVN 3 | Surface acc. Rivin eq.(3) | 16.61967 | 24.92950 | 33.23934 | 41.54917 | 49.85900 | 58.16884 | 66.47867 |

| 2D-MVN 3 | Surface approx1 eq.(7) | 16.66391 | 24.99586 | 33.32782 | 41.65977 | 49.99173 | 58.32368 | 66.65564 |

| 2D-MVN 3 | Surface approx2 eq.(8) | 16.66409 | 24.99613 | 33.32818 | 41.66022 | 49.99227 | 58.32431 | 66.65636 |

2-dim MVN 4:

| 2D-MVN | Formula | dm=0.50 | dm=0.75 | dm=1.00 | dm=1.25 | dm=1.50 | dm=1.75 | dm=2.00 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D-MVN 4 | Surface exact eq.(5) | 6.87197 | 10.30796 | 13.74395 | 17.17993 | 20.61592 | 24.05191 | 27.48789 |

| 2D-MVN 4 | Surface acc. Rivin eq.(3) | 6.83515 | 10.25272 | 13.67029 | 17.08787 | 20.50544 | 23.92302 | 27.34059 |

| 2D-MVN 4 | Surface approx1 eq.(7) | 6.87101 | 10.30652 | 13.74202 | 17.17753 | 20.61304 | 24.04854 | 27.48405 |

| 2D-MVN 4 | Surface approx2 eq.(8) | 6.87197 | 10.30796 | 13.74395 | 17.17993 | 20.61592 | 24.05191 | 27.48789 |

2-dim MVN 5:

| 2D-MVN | Formula | dm=0.50 | dm=0.75 | dm=1.00 | dm=1.25 | dm=1.50 | dm=1.75 | dm=2.00 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D-MVN 5 | Surface exact eq.(6) | 12.98802 | 19.48203 | 25.97604 | 32.47005 | 38.96407 | 45.45808 | 51.95209 |

| 2D-MVN 5 | Surface acc. Rivin eq.(3) | 12.87278 | 19.30917 | 25.74556 | 32.18195 | 38.61834 | 45.05473 | 51.49112 |

| 2D-MVN 5 | Surface approx1 eq.(9) | 12.96426 | 19.44638 | 25.92851 | 32.41064 | 38.89277 | 45.37489 | 51.85702 |

| 2D-MVN 5 | Surface approx2 eq.(10) | 12.98802 | 19.48203 | 25.97604 | 32.47005 | 38.96407 | 45.45806 | 51.95207 |

2-dim MVN 6:

| 2D-MVN | Formula | dm=0.50 | dm=0.75 | dm=1.00 | dm=1.25 | dm=1.50 | dm=1.75 | dm=2.00 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D-MVN 6 | Surface exact eq.(5) | 14.00078 | 21.00118 | 28.00157 | 35.00196 | 42.00235 | 49.00274 | 56.00314 |

| 2D-MVN 6 | Surface acc. Rivin eq.(3) | 14.04203 | 21.06305 | 28.08407 | 35.10508 | 42.12610 | 49.14712 | 56.16813 |

| 2D-MVN 6 | Surface approx1 eq.(7) | 13.99352 | 20.99028 | 27.98704 | 34.98380 | 41.98056 | 48.97732 | 55.97408 |

| 2D-MVN 6 | Surface approx2 eq.(8) | 14.00078 | 21.00118 | 28.00157 | 35.00196 | 42.00235 | 49.00274 | 56.00314 |

However, the approximation formulas of Linderholm/Segal (7) and especially of Ramanujan (8) give you better results than our statistical numerical estimation.

Accuracy and number of statistical data points

An interesting question is how the accuracy varies with the number of data points. The problem is that with growing dimension the space we have to fill grows substantially. A first guess is that we need a certain number of data points per dimension to get a reasonable accuracy. In our case we would need 6 to 7 million points if we went to n=500. Which is many! So, let us go down to 800 points per dimension. That would mean 400.000 data points for n=500. (Such numbers are relatively common in modern Machine Learning.)

The following table shows that the relative error goes up to some percent due to the lower resolution of the MVN. The table contains values of the relative error of the evaluation of Rivin’s formula compared with values of eq. (6) for ellipsoids and eq. (5) for ellipses, evaluated for only two values of the Mahalanobis distance dm = 0.5, 2.00. The order of the the MVNs corresponds to the order given above.

| 2D/3D | axes | dm=0.50 | dm=2.00 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D | (0, 1, 2) | 0.010 | 0.009 |

| 3D | (0, 1, 3) | 0.015 | 0.025 |

| 3D | (0, 2, 3) | 0.021 | 0.019 |

| 3D | (1, 2, 3) | 0.017 | 0.017 |

| 2D | (0, 1) | 0.024 | 0.024 |

| 2D | (0, 2) | 0.021 | 0.022 |

| 2D | (0, 3) | 0.015 | 0.014 |

| 2D | (1, 2) | 0.015 | 0.018 |

| 2D | (1, 3) | 0.029 | 0.028 |

| 2D | (2, 3) | 0.011 | 0.012 |

Addendum 02/08/2026: I have tested multiple samples for 2400 data points (800 per dimension). While the relative error typically is around 1 to 3 percent, fit may go down to err_rel ≈< 0.005 , when we start with an initial 4-dimensional MVN and rotate it into its main axes system ahead of a projection to 3-im sub-spaces.

Conclusion

In this post we have used numerical means to show that Rivin’s formula based on MVN statistics indeed provides a correct value for the surface area of 2-dimensional ellipsoids in the ℝ3 and ellipses in the ℝ2. Of course, using discrete data points in our evaluation came with relative errors. But the accuracy for our numerical settings was quite convincing. This strengthens our trust in Rivin’s formua for the evaluation of the surface area of n-ellipsoids. Note however that our tests can not replace numerical evaluations for a higher number of dimensions. I will discuss this point briefly in a forthcoming post.

Links and literature

[1] I. Rivin, 2003, “Surface Area of Ellipsoids”, DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.math/0306387,

https://arxiv.org/abs/math/0306387v4

[2] I. Rivin, 2004, “Surface Area And Other Measures Of Ellipsoids”, DOI: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.math/0403375,

https://arxiv.org/abs/math/0403375

[3] J.D. Cook, 2021, “Simple approximation for surface area of an ellipsoid”, blog post at

https://www.johndcook.com/blog/2021/03/24/surface-area-ellipsoid/

[4] J.D. Cook, 2023, “Hyperellipsoid surface area”, blog post at

https://www.johndcook.com/blog/2023/09/11/hyperellipsoid-surface-area/

[5] C. E. Linderholm, A. C. Segal, 1995, “An Overlooked Series for the Elliptic

Perimeter”, Mathematics Magazine, June 1995, pp. 216-220

[6] Wikipedia article on “Perimeter of an ellipse”,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perimeter_of_an_ellipse

[7] G. P. Michon, 2004, “Spheroids & Scalene Ellipsoids”,

https://www.numericana.com/answer/ellipsoid.htm#spheroid

[8] Wikipedia article on “Ellipsoid”,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ellipsoid

[9] C. Hill, 2020, “Learning Scientific Programming with Python”, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/97811087780391.

Online excerpt regarding approximations to elliptic integrals and the surface of an ellipsoid at

https://scipython.com/books/book2/chapter-8-scipy/problems/the-surface-area-of-an-ellipsoid/

[10] Paul Masson, Independent Physicist, San Francisco, 2021, contribution at analyticphysics.com on n-dimensional ellipsoids

https://analyticphysics.com/Higher%20Dimensions/Ellipsoids%20in%20Higher%20Dimensions.htm

[11] G. J. Tee, 2004/2005, “Surface Area And Capacity Of Ellipsoids In n Dimensions”, Department of Mathematics, University of Auckland, New Zealand,

https://www.math.auckland.ac.nz/deptdb/dept_reports/539.pdf

https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/server/api/core/bitstreams/64845042-d15c-4667-9ffe-c59682665f1d/content